Interview with the anonymous for the anonymous, by Mercer Union, 21 August, 1999

MU: About yourself, what were you wearing when you thought of the idea?

I was in London having a diet coke at Mark Pimlott's studio in Old Street. Probably a Kiasma cap, Calvin Klein black t-shirt XL, old jeans with a pair of New Balance trainers (size 9 1/2 4E). The same as today except it's my birthday and I'm celebrating.

MU: We're also celebrating our move to Queen West where all the new galleries are popping up. It's exciting for us to go there. Pulling away from the centre and going to a new centre. As the first exhibition in our new Lisgar Street space, what is the exhibition about and why did you choose Toronto?

A starting point for the exhibition is that I have selected works that have been made globally by Zhang Huan in Beijing, Sam Taylor-Wood in London, Francis Alys in Mexico City, Rachel Whiteread in New York, Nobuyoshi Araki in Tokyo and Toronto. I love cities. The exhibition is based around the concept of the self portrait; the definition of self in a city; love; identity; time; performance; spiritual reflection; migration - for which the inaugural exhibition is naturally a poignant time. From Rembrandt to Chuck Close, the self portrait has been central to art. Here is a sideways view of the genre with a sense of the urban fabric at the end of the twentieth century. The exhibition starts at Mercer Union in Toronto - the mega-city - and then travels this fall to a writers' hut in Monastery, on the edge of Nova Scotia.

MU: What is the relationship between the two?

I like in-between spaces. Like your own Mercer Union logo. The last exhibitions I did were in a converted monastery in Kiev (1997) and at the Birmingham Museum of Art (1999), both titled infra-slim spaces from a quote by Marcel Duchamp about invisible spaces. The Nova Scotia proposal came at a dinner party hosted by David and Julie Moos in Alabama where he introduced me to the writer Charles Gaines and his wife, the artist Patricia Ellisor Gaines. I really liked them. He's like a new Hemingway and she's a wonderful southern belle. They really liked the exhibition in Alabama and invited me to have a show at their retreat this fall.

MU: So what would you hang in Nova Scotia?

Probably everything that is here in Toronto. From Liisa Roberts' study for Here (1998), a sound piece in the entrance, to the last piece, Mark Pimlott's polished stainless steel sculpture Nothing (1998). Except I would have to leave out the Steve McQueen video projection Five Easy Pieces (1995), as it can only be shown in museum conditions - and instead show a video by the Chapman brothers Bring me the head of ƒ(1994). I couldn't really show it publicly.

MU: Why not?

Robert Frank wouldn't approve. What did this space used to be?

MU: A refrigeration unit...

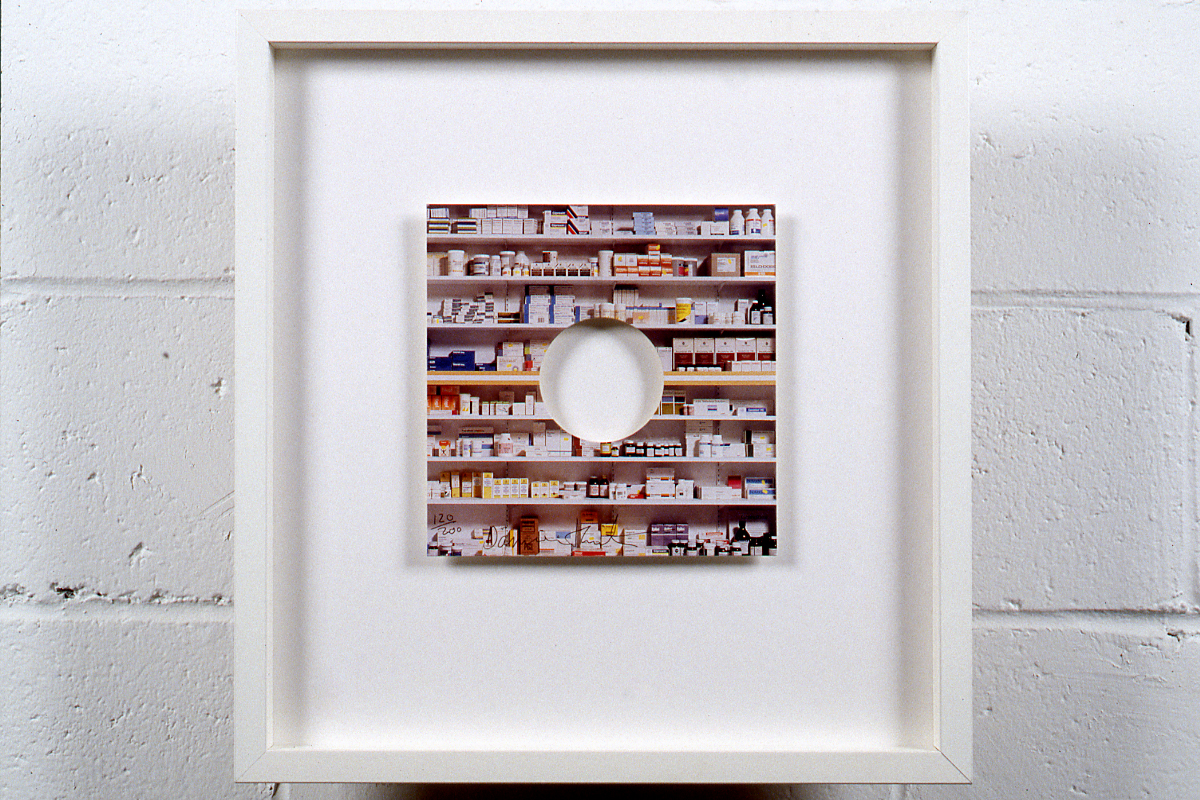

...I like the idea of recycling (laughs) - it's the basis of my project; the sense of recycling, looking at art early on in an artist's career, when the artists themselves are not so sure about their work. So if I'm in a studio, and in a situation where there might be work I really like, and I acquire it, they are never more than the price of a second-hand Saab; the price tends to be in the hundreds rather than in the thousands. But these works are something that I'm trying to keep with me, and one sense of moving around is I want to move the pieces around. And since I have custodians in different homes in London, I might lend you a work. Like Georgina Starr's seminal video Crying (1993). Or you might choose Emma Kay's The Bible from Memory (1997), a text piece that is the ultimate beginning of everyone's family tree. Or Damien Hirst's Pharmacy Edition(1994) that you could hang in your bathroom - he thinks of all those medicines as being a hierarchical portrait of the body.

MU: How did the Invisible Museum start?

The idea for "a museum without walls" was inspired by Andre Malraux: novelist, revolutionary, and France's Minister of Culture in the 1960s. He was really the first to pick up on the infinite reproducibility of art - art can go out into the world.

MU: But why invisible?

The collection is usually invisible - to my eye and memory - as they are lent to friends, artists and occasionally museums. But for a book project Invisible London, a color photograph is always taken in its new surroundings. The collection is usually experienced piece by piece in intimate, private places and this is the first time they have been brought together in Canada. It starts in Toronto and is traveling to Nova Scotia.

MU: Do you sense that you're lost on this journey?

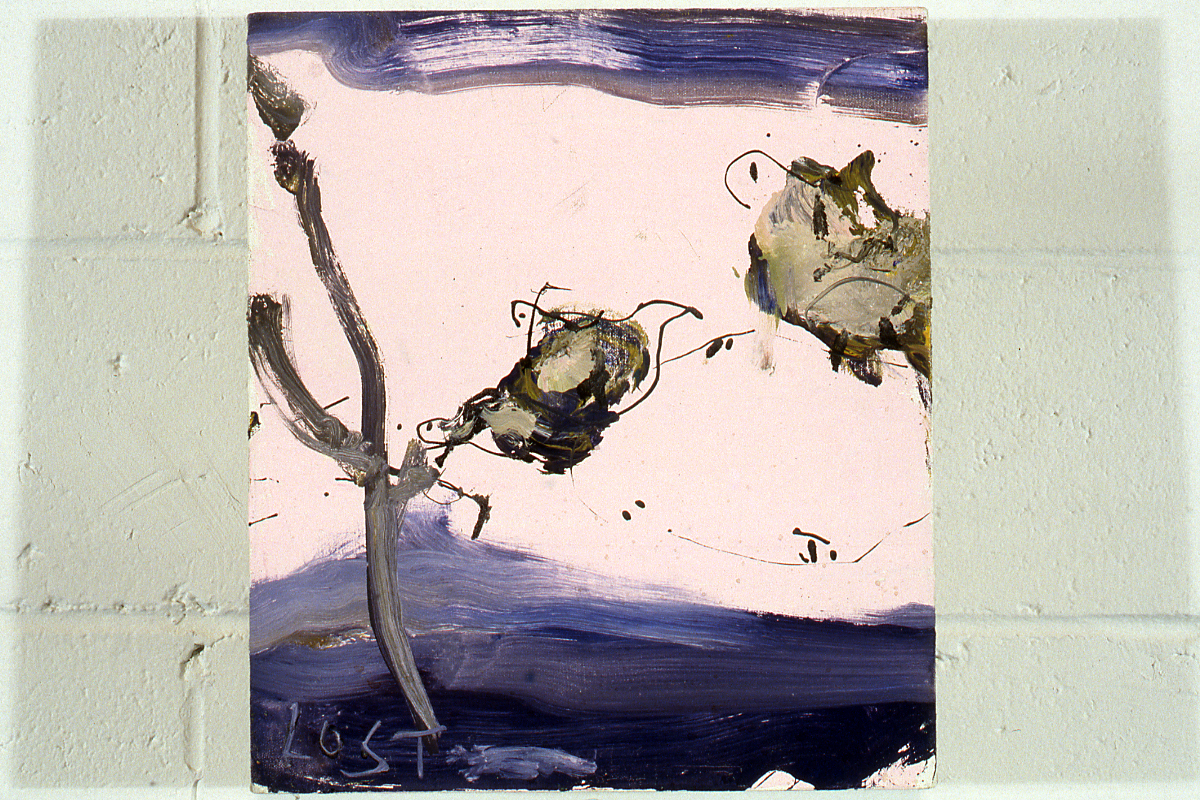

I don't think so much as lost, but I do think that coming here to Canada is about being on the edge. Incidentally, one of the works in the exhibition is Brad Kahlhamer's tiny painting Lust/Lost (1998), a dream-like space outside Tucson. I do feel that there's definitely something here that might not have a label. And in the same way I don't want to be labelled as a collector...

MU: I was going to ask you, how do you describe yourself?

As a nomad with a private collection of contemporary art.

MU: It changes your relationship to it, doesn't it, in relation to what you're talking about here?

Yes. The changing nature is important. After Nova Scotia, there are plans next year to have exhibitions in a private house in Kyoto, in Yerba Buena Centre for Arts in San Francisco, and during the 8th International Cairo Biennale at Christmas 2000, in an apartment in Cairo that hasn't been touched since the 1950s. It's a world tour that started in Kiev, and is traveling across the world, across the millennium. The final stop will be at the amazing Sir John Soane's Museum in London in late 2001. If you can look at art from a side-view, that's sometimes better than seeing it straight on.

MU: I'm lost again. Where are we?

That's the ultimate question and the start of self portrait.

MU: About yourself, what were you wearing when you thought of the idea?

I was in London having a diet coke at Mark Pimlott's studio in Old Street. Probably a Kiasma cap, Calvin Klein black t-shirt XL, old jeans with a pair of New Balance trainers (size 9 1/2 4E). The same as today except it's my birthday and I'm celebrating.

MU: We're also celebrating our move to Queen West where all the new galleries are popping up. It's exciting for us to go there. Pulling away from the centre and going to a new centre. As the first exhibition in our new Lisgar Street space, what is the exhibition about and why did you choose Toronto?

A starting point for the exhibition is that I have selected works that have been made globally by Zhang Huan in Beijing, Sam Taylor-Wood in London, Francis Alys in Mexico City, Rachel Whiteread in New York, Nobuyoshi Araki in Tokyo and Toronto. I love cities. The exhibition is based around the concept of the self portrait; the definition of self in a city; love; identity; time; performance; spiritual reflection; migration - for which the inaugural exhibition is naturally a poignant time. From Rembrandt to Chuck Close, the self portrait has been central to art. Here is a sideways view of the genre with a sense of the urban fabric at the end of the twentieth century. The exhibition starts at Mercer Union in Toronto - the mega-city - and then travels this fall to a writers' hut in Monastery, on the edge of Nova Scotia.

MU: What is the relationship between the two?

I like in-between spaces. Like your own Mercer Union logo. The last exhibitions I did were in a converted monastery in Kiev (1997) and at the Birmingham Museum of Art (1999), both titled infra-slim spaces from a quote by Marcel Duchamp about invisible spaces. The Nova Scotia proposal came at a dinner party hosted by David and Julie Moos in Alabama where he introduced me to the writer Charles Gaines and his wife, the artist Patricia Ellisor Gaines. I really liked them. He's like a new Hemingway and she's a wonderful southern belle. They really liked the exhibition in Alabama and invited me to have a show at their retreat this fall.

MU: So what would you hang in Nova Scotia?

Probably everything that is here in Toronto. From Liisa Roberts' study for Here (1998), a sound piece in the entrance, to the last piece, Mark Pimlott's polished stainless steel sculpture Nothing (1998). Except I would have to leave out the Steve McQueen video projection Five Easy Pieces (1995), as it can only be shown in museum conditions - and instead show a video by the Chapman brothers Bring me the head of ƒ(1994). I couldn't really show it publicly.

MU: Why not?

Robert Frank wouldn't approve. What did this space used to be?

MU: A refrigeration unit...

...I like the idea of recycling (laughs) - it's the basis of my project; the sense of recycling, looking at art early on in an artist's career, when the artists themselves are not so sure about their work. So if I'm in a studio, and in a situation where there might be work I really like, and I acquire it, they are never more than the price of a second-hand Saab; the price tends to be in the hundreds rather than in the thousands. But these works are something that I'm trying to keep with me, and one sense of moving around is I want to move the pieces around. And since I have custodians in different homes in London, I might lend you a work. Like Georgina Starr's seminal video Crying (1993). Or you might choose Emma Kay's The Bible from Memory (1997), a text piece that is the ultimate beginning of everyone's family tree. Or Damien Hirst's Pharmacy Edition(1994) that you could hang in your bathroom - he thinks of all those medicines as being a hierarchical portrait of the body.

MU: How did the Invisible Museum start?

The idea for "a museum without walls" was inspired by Andre Malraux: novelist, revolutionary, and France's Minister of Culture in the 1960s. He was really the first to pick up on the infinite reproducibility of art - art can go out into the world.

MU: But why invisible?

The collection is usually invisible - to my eye and memory - as they are lent to friends, artists and occasionally museums. But for a book project Invisible London, a color photograph is always taken in its new surroundings. The collection is usually experienced piece by piece in intimate, private places and this is the first time they have been brought together in Canada. It starts in Toronto and is traveling to Nova Scotia.

MU: Do you sense that you're lost on this journey?

I don't think so much as lost, but I do think that coming here to Canada is about being on the edge. Incidentally, one of the works in the exhibition is Brad Kahlhamer's tiny painting Lust/Lost (1998), a dream-like space outside Tucson. I do feel that there's definitely something here that might not have a label. And in the same way I don't want to be labelled as a collector...

MU: I was going to ask you, how do you describe yourself?

As a nomad with a private collection of contemporary art.

MU: It changes your relationship to it, doesn't it, in relation to what you're talking about here?

Yes. The changing nature is important. After Nova Scotia, there are plans next year to have exhibitions in a private house in Kyoto, in Yerba Buena Centre for Arts in San Francisco, and during the 8th International Cairo Biennale at Christmas 2000, in an apartment in Cairo that hasn't been touched since the 1950s. It's a world tour that started in Kiev, and is traveling across the world, across the millennium. The final stop will be at the amazing Sir John Soane's Museum in London in late 2001. If you can look at art from a side-view, that's sometimes better than seeing it straight on.

MU: I'm lost again. Where are we?

That's the ultimate question and the start of self portrait.