SPACE invites one artist to produce a yearlong series of images for a public-facing billboard located on the east façade of Mercer Union.

Mercer Union’s SPACE billboard commission has invited artist Lotus Laurie Kang for its 2022–23 season for a yearlong series titled, Mother Always Has a Mother. Known for her sprawling installations and distinctive material repertoire, Kang’s practice is a dialogue with entropy. Elegantly disordered and richly layered, her site-sensitive works explore the relational bonds between time, personal history, and cultural knowledge. They seek to disrupt a human-centred perspective of the world with a broad curiosity for life and matter tangled in states of exchange that produce and are reproduced by their environments.

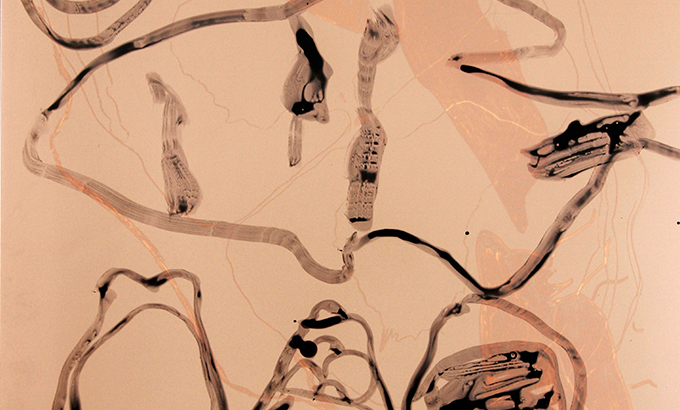

Sunlight, Kang’s earliest collaborator, accumulates and rewrites much of the photographic works for which she is best known. While materials like steel, silicone, perishable or manufactured goods assist as other forms of carriers. In Mother Always Has a Mother the artist offers something new, working for the first time with textiles to produce a series of three sculptural works that translate ideas of inheritance, loss, and lineage through the vernacular of seams, frayed edges, and folds. A deconstructed industrial grain bag suggests the pattern from which Kang assembles the works in this series in heavy cloth. Each edition features reproductions of renderings by the artist in photographic chemistry. Conjuring memory of her paternal grandmother, who opened a seed and grain shop in Seoul after fleeing North Korea, the artist contemplates the grain bag as evidence of an accelerated world. Mother Always Has a Mother considers what we carry by revealing the tension between conscious memory and embodied knowledge: one coded in time, the other in flesh; each in continual transformation.

Burnt Orange (2022) is the second edition in the yearlong series; accompanying the work is a text written by Diana Seo Hyung Lee.

Burnt Orange: Sticky, Mothers

When my son was 20-months-old, he would let out the sounds “mm-ma-ma,” not to call out to me, but to express need. Perhaps the “m” sound is a phonetic equivalent for want of care that attaches itself to the figure of the mother—the one we turn towards for our needs. I started wondering, or rather it dawned on me recently that I might have named my son “Mark” because I wanted this connection mimicked in his name.

For much of my life, my mother has treated me less as her daughter and more as someone who would later become a wife, daughter-in-law, and mother. I have an early memory of resisting to bathe and my mother saying to five year old me, “if you are not in the practice of taking care of your hygiene, one day your mother-in-law will wonder, ‘who is her mother that she does not know how to take care of herself?’” I remember acquiescing to her roughly scrubbing my skin and making me sit in what felt like boiling water after she gave me this type of talking-to.

Years passed but her words would keep echoing within me, and I thought, if I never became anyone’s daughter-in-law or mother, perhaps my mother and I would have a chance at a relationship. I mistakenly believed that my desire to have a child was a sign of finally having let her go, but my son’s name stands as evidence, making a mockery of me; I have not let go of her, I have just created a way to call out to her without addressing her.

Whenever I call Mark, I feel the sticky vibration of the “ma” touch the inside and outside of my lips. It feels soothing and I want to keep calling to him. For a while I savored the days before he could speak and others would have to ask me for his name. I’d turn to them and say with glee, “His name is Mark.” I was delighted the day he finally said to me “I’m Mark!”, taking his chubby index finger pointed at his round, protuberant toddler belly. “Yes, you are!” I exclaimed, embracing him. I could pretend that my enthusiasm was at his articulation, but I knew that it was because it felt as if I had finally received a response, not that my son had become my mother but that his confirmation affirmed my want of maternal care—it is not futile, nor shameful.

I realize that through Mark I have arrived at a new vantage from which to move through the personal grief between my mother and me. I think of all the words for mother that I know: mama, mom, mum, mère, 엄마 (umma) and I envision them like a bag, vessel, carrier, and holder. I understand that my mother has also had a mother, that I am a thread within a dense weave that holds us together, our memories as well as our futures.

It is not an accident that my child, like my mother in her youth, is fearful of bubbles that form on the surface of milk. She used to say to me, “너도 나중에 애 낳고 키워봐 (wait till you have and raise your own child).” While puncturing every bubble with a spoon, I mutter under my breath “엄마, 나도 이제 엄마야 (mother, I too, am now a mother).”

— Diana Seo Hyung Lee