East and West Galleries

Rethinking History, curated by Carol Podedworny, brings together a group of artists whose work, whether concerned with issues of authority, expose, subjecthood, challenges the construction of the dominant History of the West.

The artists participating in the exhibition are: John Abrams, Stephen Andrews, Robert Houle, Sara Leydon, Edward Poitras and Jane Ash Poitras.

Beginning with a perspective informed by personal experience, each of these artists present alternative histories which challenge traditional western notions of art and who has been allowed to speak through art.

A panel discussion with Sara Leydon, Edward Poitras, Jane Ash Poitras and Carol Podedworny will take place on March 12 at 7 pm.

Brochure Text:

Rethinking History

Rethinking History is an exhibition in which History began as monolith, and in which other histories became the focus of truth.

The white-European-male-as-norm ideology presents a world view centered upon itself, and refers to the Other as an element of either support or detriment to its own achievements, or alternatively as simply absent. In a position of dominance in terms of global economic, political and social realities, the white European male wields the power through the control of language and writing to determine History. The validity of one History has become increasingly difficult to accept. All of the artists in this exhibition align themselves with cultures and/or communities which have traditionally functioned on the margin. Their work, whether concerned with issues of authority, expose, subjecthood, or otherwise, ultimately challenges the 'History of the West' not only in terms of its writing, but also of its actual lived experience. By either deconstructing the 'myths of modernity' or, alternatively, by revising that history by infusing a perspective from the Other, these artists have persuasively assisted the rethinking and hence, rewriting, of history.

The histories presented by John Abrams, Stephen Andrews, Robert Houle, Sara Leydon, Edward Poitras, and Jane Ash Poitras are of an individual and collective nature. Beginning with a perspective informed by personal experience, the statements expand to encompass a cultural and/or community response. For example, Houle's appropriation of Benjamin Wests' The Death of Wolfe was inspired by a recurrent statement of Houle's grandfather's: "When history was made, an Indian was present". Yet, the implications for the validation of the role and place of the First Nations in much of early Canadian history are clear. For all of the artists in the exhibition, a personal/communal alignment appears appropriate for "without the reconciliation of the self to the community we cannot invent ourselves". 1

In the process of defining, or redefining, themselves in terms other than mainstream history would suggest, the artists in this exhibition have examined that history and have done so via a selective process. History is a result of both remembering and forgetting,2 and the artists in Rethinking History have been selective in the images and messages they have reconstituted. In paintings that are stripped of colour and magnificent in size, Abrams demands that we reconsider the position of the dominant. He has chosen objects of dominant culture and presented them as shadows which follow behind us, which never really leave us, though they come and go depending upon the 'light' in which we find ourselves. The gigantic printing press and helmet serve as metaphors for white European capitalist expansion in an industrial world, while the portrait of the child injects a measure of optimism for the coming millennium. As critique and prophecy, Abrams' paintings reveal the artist's role as reappraiser. Alternatively, the other artists in the exhibition have either critically recollected history, quoting and appropriating at will, as do Houle and Poitras, or have expressed a kind of amnesia which reflects a particular specificity, as do Andrews, Leydon, and Ash Poitras.

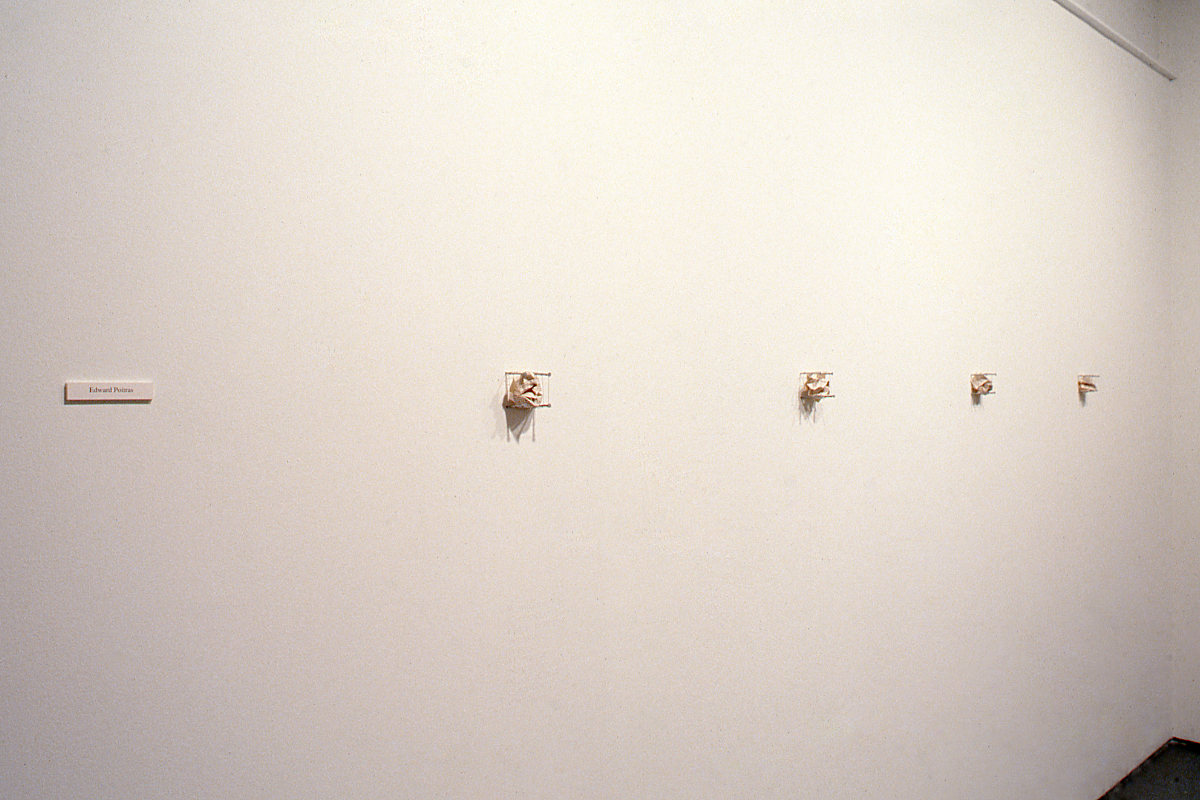

Houle and Poitras have appropriated from the dominant community images and citations which, when reconstructed or presented in new contexts, have the ability to critique a past method of thought. Houle, for example, has borrowed references from two distinct periods of modernist art history. Poitras has cited directly from a western text. In each instance, the artists have laid bare colonialist actions, in the first place as a consequence of obsolescence, and in the second as the result of government instituted genocide. In Houle's Kanata, the 'grandness' of oil painting--its colours, the colours of history--have not been included except for that of the 'Indian'. In Poitras' Small Matters, pages from Bury My Heart at Wounded Kneeare enclosed within wire 'fences' which have been nailed to the wall. The pages refer to four 19th century massacres of Native Americans; Wounded Knee, Summer Snow, Trail of Tears, and Sand Creek. A partial list of the lost tribes is stenciled below the wire enclosures.

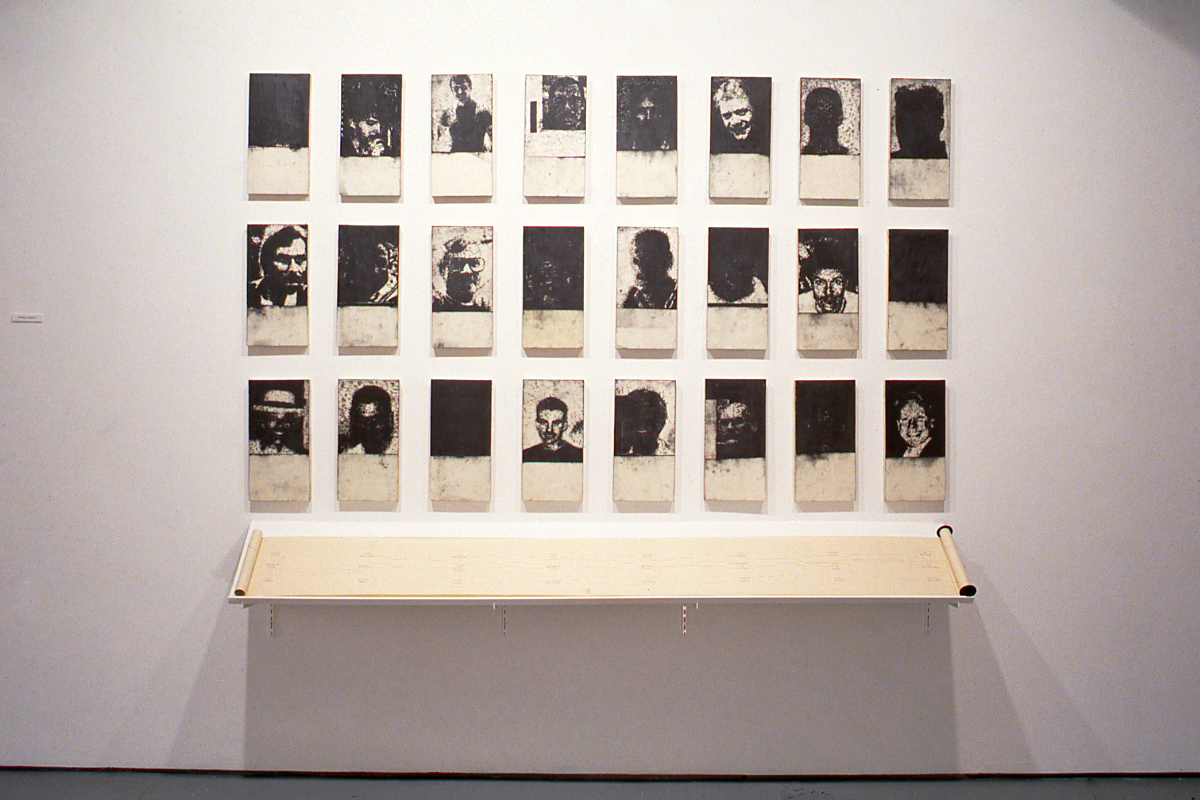

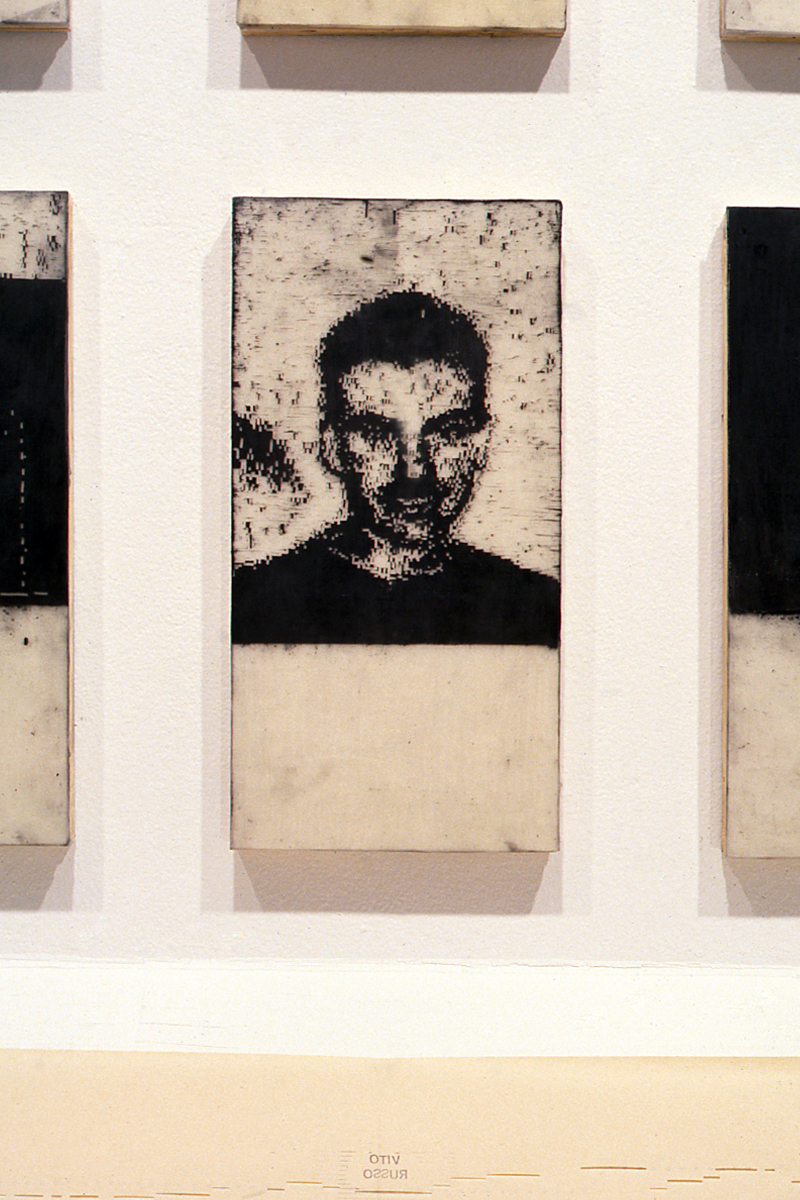

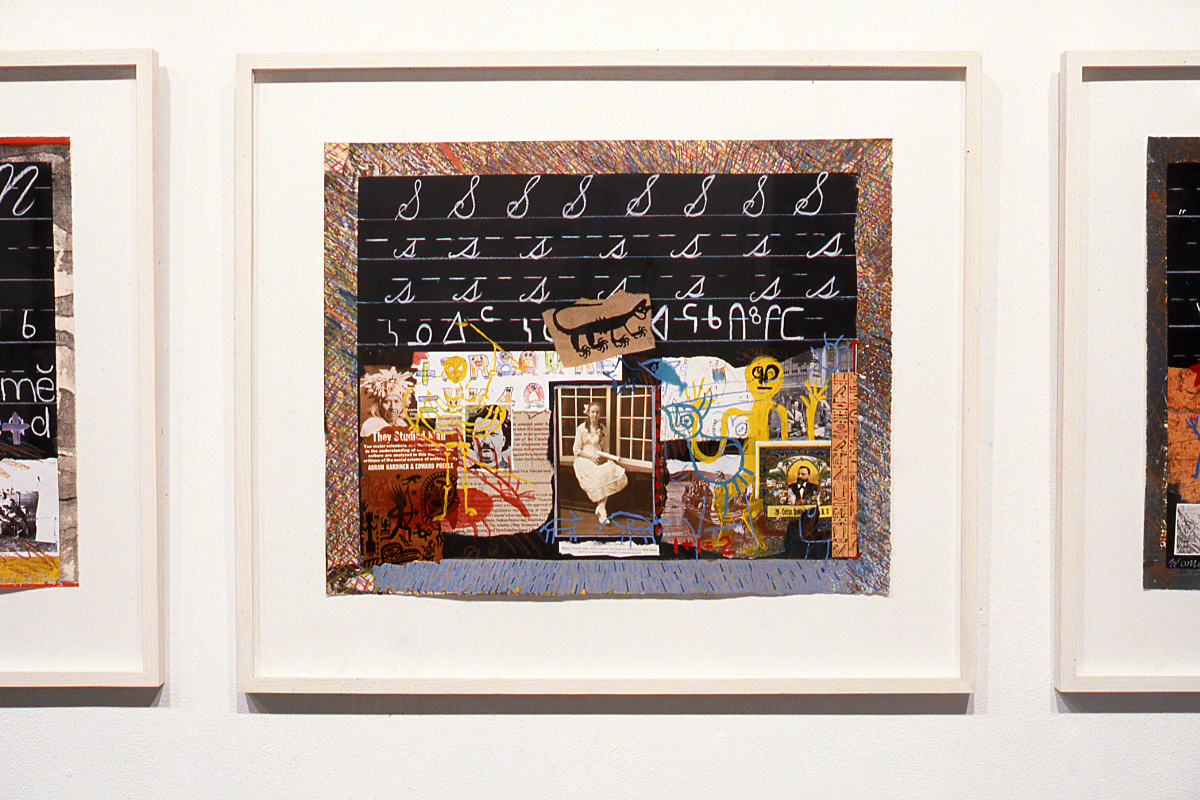

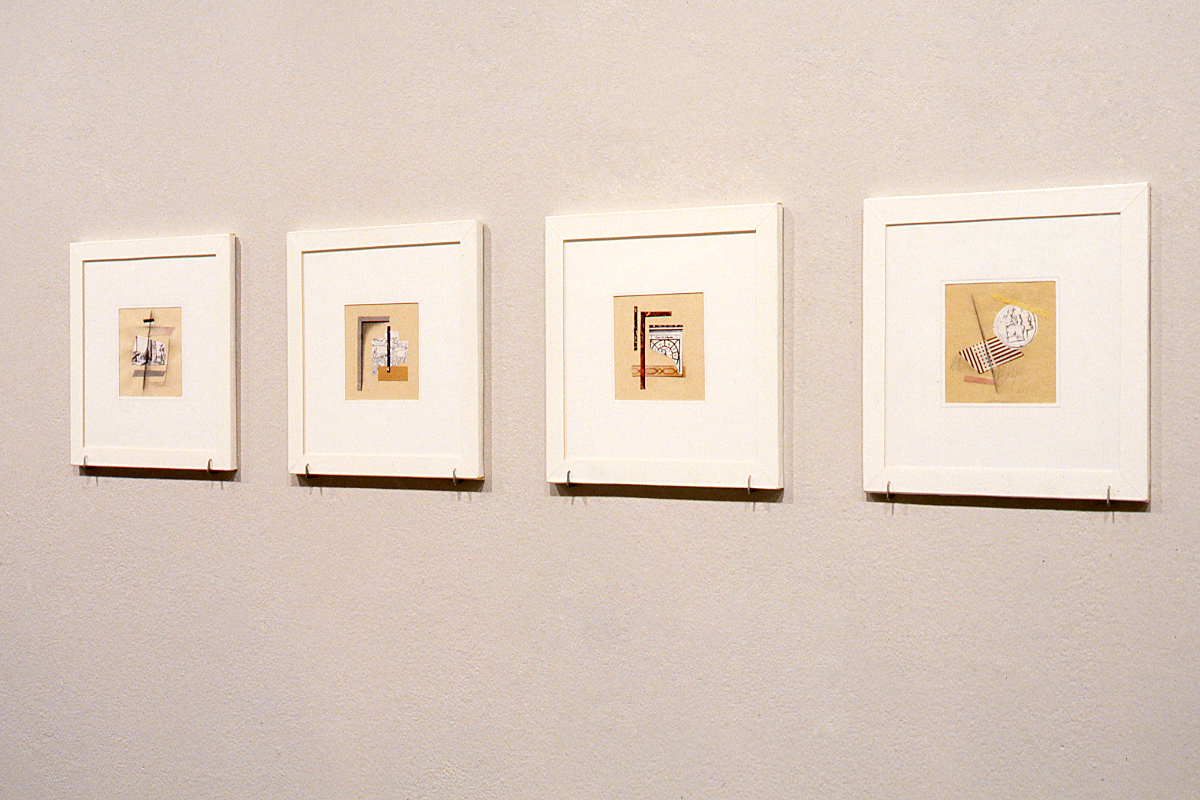

The work of Andrews, Leydon, and Ash Poitras critically alters the path of history as established thus far by infiltrating that history with new, disparate histories which neither legitimate nor follow that of the accepted norm. Each of these artists has chosen to present images which are not of the mainstream-- Andrews with 'faxed' portraits from a newspaper, Leydon with reproductions from 'minor' arts such as illustration and design, and Ash Poitras with an eclectic selection of images and texts drawn from both dominant and marginalized sectors. The transformation of these visual documents into works of art similarly denies the ideology of a progressive teleology inherent in modernist art history.3 Andrews' portraits of men who have died of AIDS or AIDS related causes, appear at a distance to be 'shot' out of a fax machine, they are however, the result of a process of scratching into tablets layered with beeswax and graphite requiring hours of labour to complete. The method is a labour of love--of intense, time-consuming work, associated with embroidery and quilting--again suggesting a non fine art affiliation. Leydon's collages, while combining a variety of non-high art images, are moreover 'framed' with tape as if they were laboratory specimens prepared for scrutiny under a microscope. Ash Poitras' collages similarly reject a western conception of the Work of Art. Situating her images on an implied blackboard, Ash Poitras uses the primary teaching implement of the white educational system whose history denied and maligned her concept of herself as a Native Canadian, in order to teach us the lessons she has subsequently learned--of pride and place and identity. Andrews, Leydon, and Ash Poitras by denying the constraints of the mainstream, and by either directly criticizing or overtly contesting (via statements of difference) the status quo, have managed to validate their particular positions of resistance as eminently powerful and ever present.

A common thread throughout the work of all of the artists in Rethinking History is the creation of a narrative which is not linear but fractured, diachronic, expressive of substantive moments of cultural/communal specificity. In keeping with this manner of visual history-making the artists have created works which reflect this fragmented nature. On the one hand, each work is composed of several separate pieces; Abrams has created a series of eighteen paintings, three of which are included in the exhibition. From Andrews' series of ninety-five individual portraits, twenty-four are included. Houle's painting is comprised of four panels, Leydon's Eidilon consists of twenty collages, and so on. On the other hand, the number of images gathered within each work are also able to function independently. Employing objects, portraits, artistic style, mnemonics, memorials, and the alphabet each artist creates works which can act individually or as a series in order to present their message. This fragmentary character is suggestive of continuity. As a variety of technical devices were employed by early modernist painters to intimate extension beyond the space defined by the picture plane, and by later artists to reveal and acknowledge the two-dimensional surface of illusion, the artists in this exhibition have utilized devices which indicate a contemporary view of time and space and the work of art. Consistent with Derrida's notion of the trace--of everything being not just present or absent but past, present, and future at once --these works, in their openness to addition or deletion, intimate an origin, a current moment and a future.

The artists in Rethinking History were brought together because they share a common desire to challenge one mode of thought and, to change what and who history is, thereby enabling revision for the past and inclusion for the future. This is not a move toward multicultural /racial /gender homogeneity, but rather a celebration and a self-validation of specificity.

- Carol Podedworny

Notes:

I . Lucy R. Lippard, Mixed Blessings: New Art in Multicultural America, (New York: Pantheon Books, 1990), p. 21

2. Mark A. Chetham, Remembering Postmodernism Trends in Recent Canadian Art, (Toronto, Oxford, New York: O~ford University Press, 1991)

3. For a definition of 'modernism' as referred to in this essay, see Brian Wall is, 'What's Wrong with this Picture? An Introduction', Art After Modernism Rethinking Representation, (New York: the Museum of Contemporary Art, 1984), p. xii.

Kate Taylor

The Globe and Mail, March 1992

As the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus's arrival on this continent wears on, we will see more and more art shows about the meaning of the European presence to the people who were here first. Beside the angry sloganeering that has thus far characterized efforts to deal with the issue in galleries, Rethinking Histories stands out like a beacon of common sense.

The first strength of this show at the Mercer Union is that it rethinks all kinds of histories--native, female, homosexual and, most crucially, artistic. While in her brief essay ' curator Carol Podedworny makes the predictable political point that these are artists speaking from the margins of white male culture, this show is not simply a litany by the dispossessed. For the most part, these are artists who have as much to say about art as they do about social neglect and have found intelligent ways of marrying the two. While there are a few weak links in the selection generally the works complement each other in their analysis of dominant peoples and dominant images.

For example, Podedworny has hung Robert Houle's large canvas Kanata with John Abrams's mighty black and white images of a printing press, a Roman helmet and a child's face. In Kanata, a central panel featuring a monochromatic copy of Benjamin West's Death of Wolfe--in which only the figure of the squatting Indian brave has been coloured in--is flanked by two abstract bands of colour, one red and one blue. The copy of West's painting is an obvious reference to the Indian's role as an observer rather than participant in history, and the whole painting takes the configuration of a flag, that trademark of conquest. But what is perhaps a rather simple critique of colonization is broadened into a tidy summary of the victory of the domineering image, in western art, from history painting to abstraction. It is exactly that victory that Abrams is exposing in his paintings which, like Houle's, emphatically illustrate the power they reject.

Similarly, the combination of Edward Poitras's tiny wall pieces about genocide -- little metal holding pens filled with crumbled pages from Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee -- with Stephen Andrews's Facsimile, a series of fax-like portraits of people who have died of AIDS inscribed on beeswax, reveals both artists as quiet memorialists, acutely aware of the ellipses in remembering.

As Canada renegotiates its relationship with the aboriginal peoples, Rethinking History may give those looking for political messages room for hope; but, more importantly for an art show, it makes a strong argument for placing native work in the contemporary mainstream. Until April 11.