There's No Place Like Here

My friend has a silver sticker adhered to the inside of his front door which reads, THERE IS NO PLACE LIKE HERE. True always, self-evident even, and yet this glittery assertion manages to startle with each encounter. The fact that my friend's door opens on to the shipping container in which he lives may augment my disorientation, but if I were to peel off the sticker and smack it on his neighbour's door instead, I would be rapt anew.

With Placecards, a group of artists engages the notion of place less as an intellectual identification than as a private empathy, less as an occupation than a preoccupation, and always with the insistence upon singularity. Indeed, there is no place like here. Or here. Or here. Each may be conjured only as a precarious mergence of public and private activities and desires. Domains are situated through observation, infiltration, chance encounter, and the minutiae of daily existence. Space is not something to be mapped, but something to fold oneself into, to press against, to slice through, to sit beside. For these artists, kingdoms are more likely to be determined by throwing your coat over the chair than by pissing around the perimeter, and one's presence in a space always alters it.

With his Landscapes and Cityscapes videos, Chris Sollars documents the results of his off-screen soccer ball kicking, following the wandering ball as it soars into environments both rural and urban. There is a sweetness to this gesture which confounds its provenance; an aggressively macho team sport condensed into a joyful, private activity, at once dignified and hilarious, assertive yet remarkably unobtrusive, sexy and lame. It is a gesture of youthful expansiveness. Ricocheting off an ATM, rebounded by a jubilant doorway loiterer, soaring over a field of cows, the soccer ball is transcendent.

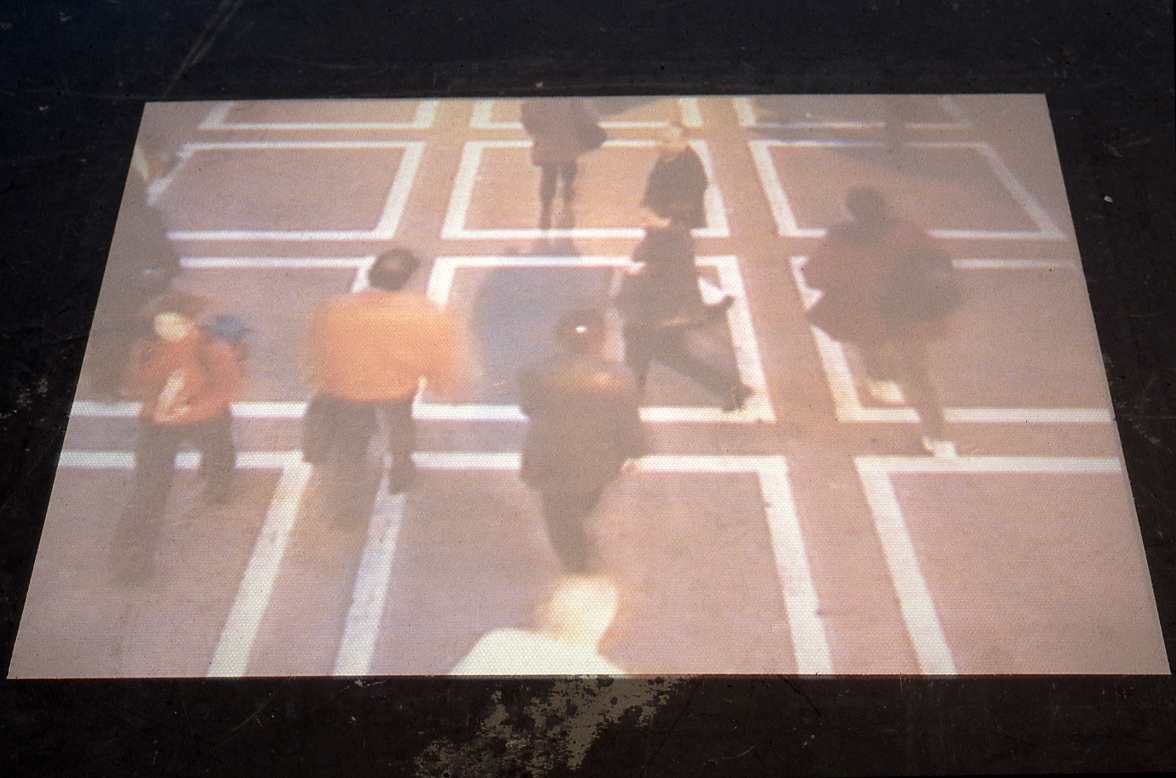

A languorous passage of time reveals another sort of transcendence in Germaine Koh's Side piece. Koh visually documents the occupation of two public benches by a group of four men while simultaneously recording the incidental audio of her own apartment where the camera is located. Watching Koh's clandestine images, we suffer an uneasy complicity. Two worlds unfold beside one another, separated by disturbing notions of privacy and economics. Yet, as days and nights pass, the worlds, almost imperceptibly, align. Eating, sleeping, reading, talking and sitting in silence, the bench and apartment dwellers fall into step. The mundane ascends to the monumental when a fighter jet streaks across the sky; the men crane their necks as Koh and her partner gasp in awe. The two worlds are companions, side pieces to one another. Time stands strangely still in Arthur Kleinjan's Paris Looks, a collection of images of tourists posing for their fellow travelers in front of Sacré-Coeur. Kleinjan captures his subjects from the position of their greatest vulnerability, above and behind, isolated from their camera-toting friends and they themselves are unaware of Kleinjan's activity. But as in Koh's video, quiet dignity levels invasiveness. Ultimately, the intimate act of posing for a friend or lover resists colonization. Kleinjan can record the image but he can not participate in the ritual of private confirmation the treasured snapshot affords.

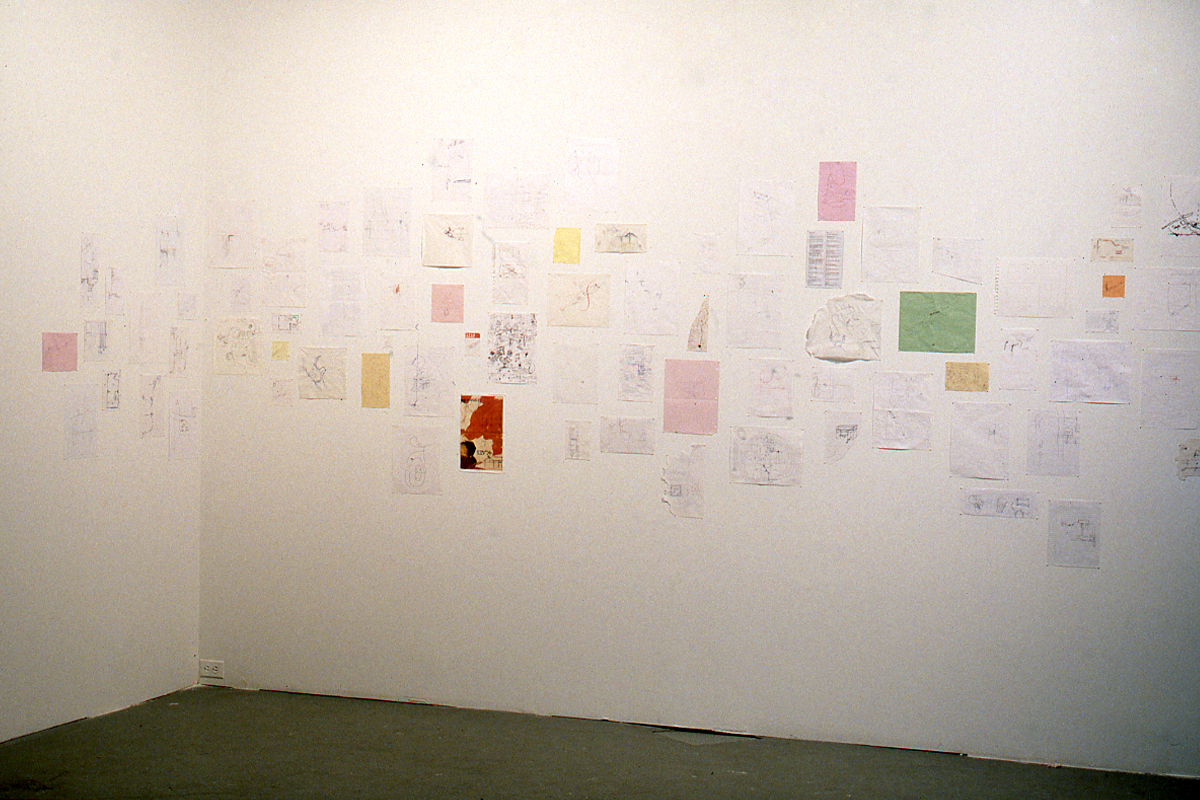

Katherine Harvey also must be content with artifacts untethered from their locus. Getting There From Here is a sprawling archive of hastily scrawled maps, urgent transactions accompanied at one time by mutual understanding, now floating abstractly through an unfamiliar space. These delicate found remnants trace a profound desire for a shared sense of orientation. I am compelled to decipher the anxious Yukon Tragedy. What tragedy? Whose death? In the morning, was it? The drawing keeps its secrets and I am left to construct my own fiction.

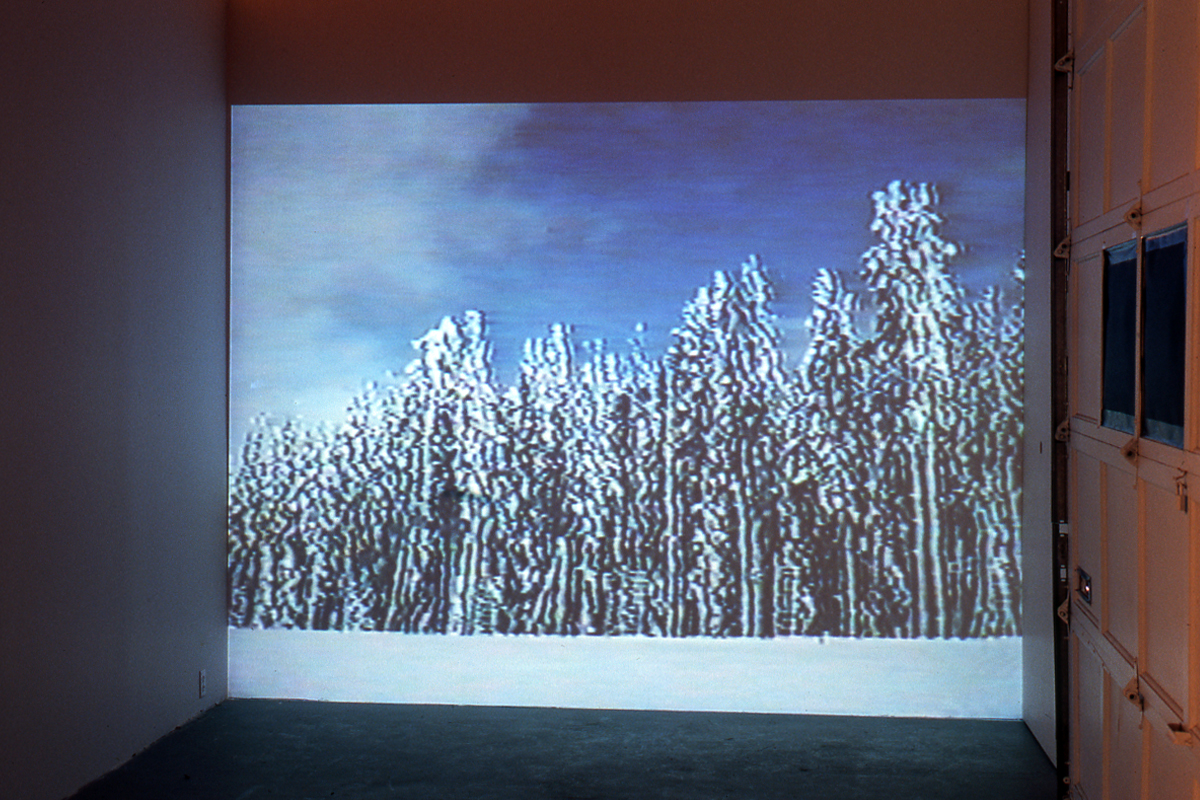

Jennifer McMackon surrenders herself to such personal narratives. In Kokohala, she casually records the winter wonderland of the Kokohala Pass as seen from the window of a traveling car. Deftly utilizing the scene's slippery depth of field, McMackon summons an excruciating contrast; brittle snow-laden pines pierce a frigid blue sky; black, skeletal trunks impossibly precise against a cloud-smeared backdrop. Accompanied by the peppy enthusiasm of the music on the car radio, space distorts, shifting between real and miniature versions of itself. I acquiesce. I sink into the car door, drop my head against the window and succumb to McMackon's dreamy meditation.

Scale similarly functions as a portal for interpretation in many of Amy Wilson's Drive-by Shooting photographs. In Apartment, Jewelry and Clock Radios, Wilson documents a type of low-rise, modernist, apartment building common to Los Angeles. En masse, slight architectural gestures amplify, insisting upon an identity, demanding community. Wilson complies. Her titles impose diminutive domestic forms upon the larger built environment; pendulous light fixtures mutate into earrings, cantilevered floors into clock radios. The familiar suburban environment becomes contingent, mutable, absurd.

I think about my friend in his container, about Germaine Koh in her apartment, and Jennifer McMackon and Amy Wilson in their cars. I imagine Katherine Harvey and Chris Sollars wandering through their cities. I see Arthur Kleinjan staked out on a rooftop. I know there are no places like these. And I know when Chris Sollars kicks his soccer ball, it floats, if only momentarily, above the gorgeous expanse of the city and our idea of our place in the world floats with it.

My friend has a silver sticker adhered to the inside of his front door which reads, THERE IS NO PLACE LIKE HERE. True always, self-evident even, and yet this glittery assertion manages to startle with each encounter. The fact that my friend's door opens on to the shipping container in which he lives may augment my disorientation, but if I were to peel off the sticker and smack it on his neighbour's door instead, I would be rapt anew.

With Placecards, a group of artists engages the notion of place less as an intellectual identification than as a private empathy, less as an occupation than a preoccupation, and always with the insistence upon singularity. Indeed, there is no place like here. Or here. Or here. Each may be conjured only as a precarious mergence of public and private activities and desires. Domains are situated through observation, infiltration, chance encounter, and the minutiae of daily existence. Space is not something to be mapped, but something to fold oneself into, to press against, to slice through, to sit beside. For these artists, kingdoms are more likely to be determined by throwing your coat over the chair than by pissing around the perimeter, and one's presence in a space always alters it.

With his Landscapes and Cityscapes videos, Chris Sollars documents the results of his off-screen soccer ball kicking, following the wandering ball as it soars into environments both rural and urban. There is a sweetness to this gesture which confounds its provenance; an aggressively macho team sport condensed into a joyful, private activity, at once dignified and hilarious, assertive yet remarkably unobtrusive, sexy and lame. It is a gesture of youthful expansiveness. Ricocheting off an ATM, rebounded by a jubilant doorway loiterer, soaring over a field of cows, the soccer ball is transcendent.

A languorous passage of time reveals another sort of transcendence in Germaine Koh's Side piece. Koh visually documents the occupation of two public benches by a group of four men while simultaneously recording the incidental audio of her own apartment where the camera is located. Watching Koh's clandestine images, we suffer an uneasy complicity. Two worlds unfold beside one another, separated by disturbing notions of privacy and economics. Yet, as days and nights pass, the worlds, almost imperceptibly, align. Eating, sleeping, reading, talking and sitting in silence, the bench and apartment dwellers fall into step. The mundane ascends to the monumental when a fighter jet streaks across the sky; the men crane their necks as Koh and her partner gasp in awe. The two worlds are companions, side pieces to one another. Time stands strangely still in Arthur Kleinjan's Paris Looks, a collection of images of tourists posing for their fellow travelers in front of Sacré-Coeur. Kleinjan captures his subjects from the position of their greatest vulnerability, above and behind, isolated from their camera-toting friends and they themselves are unaware of Kleinjan's activity. But as in Koh's video, quiet dignity levels invasiveness. Ultimately, the intimate act of posing for a friend or lover resists colonization. Kleinjan can record the image but he can not participate in the ritual of private confirmation the treasured snapshot affords.

Katherine Harvey also must be content with artifacts untethered from their locus. Getting There From Here is a sprawling archive of hastily scrawled maps, urgent transactions accompanied at one time by mutual understanding, now floating abstractly through an unfamiliar space. These delicate found remnants trace a profound desire for a shared sense of orientation. I am compelled to decipher the anxious Yukon Tragedy. What tragedy? Whose death? In the morning, was it? The drawing keeps its secrets and I am left to construct my own fiction.

Jennifer McMackon surrenders herself to such personal narratives. In Kokohala, she casually records the winter wonderland of the Kokohala Pass as seen from the window of a traveling car. Deftly utilizing the scene's slippery depth of field, McMackon summons an excruciating contrast; brittle snow-laden pines pierce a frigid blue sky; black, skeletal trunks impossibly precise against a cloud-smeared backdrop. Accompanied by the peppy enthusiasm of the music on the car radio, space distorts, shifting between real and miniature versions of itself. I acquiesce. I sink into the car door, drop my head against the window and succumb to McMackon's dreamy meditation.

Scale similarly functions as a portal for interpretation in many of Amy Wilson's Drive-by Shooting photographs. In Apartment, Jewelry and Clock Radios, Wilson documents a type of low-rise, modernist, apartment building common to Los Angeles. En masse, slight architectural gestures amplify, insisting upon an identity, demanding community. Wilson complies. Her titles impose diminutive domestic forms upon the larger built environment; pendulous light fixtures mutate into earrings, cantilevered floors into clock radios. The familiar suburban environment becomes contingent, mutable, absurd.

I think about my friend in his container, about Germaine Koh in her apartment, and Jennifer McMackon and Amy Wilson in their cars. I imagine Katherine Harvey and Chris Sollars wandering through their cities. I see Arthur Kleinjan staked out on a rooftop. I know there are no places like these. And I know when Chris Sollars kicks his soccer ball, it floats, if only momentarily, above the gorgeous expanse of the city and our idea of our place in the world floats with it.

Stacey Lancaster