With 0.001 PERCENT VOLUME Dave Dyment brings together three solo exhibitions: Ben Woodeson's Point Blank, Levin Haegele's, Glow Space and Myfanwy Ashmore's enarmoured euphorbia. In a discussion that looks at critical art practices from the late sixties and early seventies, Dyment situates the work of Woodeson, Haegele and Ashmore as a contemporary re-examination of issues and the aesthetic of early minimal and conceptual art practices, but one that is, instead, less confrontational and is imbued with a welcoming invitation and sense of play.

"There is a warmth, domesticity and naiveté at play in 0.001 PERCENT VOLUME that is absent in many of the boundary breaking "nothing works" of the sixties. A simple seamstress' pin, a child's voice, debris on one's boots - these couldn't be more different from the grandiloquence of minimalism or the chilly detachment of conceptualism. These restrained and understated gestures have the ability to open up a striking set of possibilities with the utmost economy of means." (excerpt from brochure essay by Dave Dyment)

Installations should empty rooms, not fill them – Robert Smithson ¹

Much is being made about Nothing these days. Bookstores carry numerous volumes on the history of zero, Seinfeld brought the discussion of the non-narrative to water-coolers everywhere² and museums around the world are presently traveling ambitious historical overviews with titles like Nothing, Nothing Matters and The Big Nothing. It’s hard not to get sucked in by the vacuum. It’s a near irresistible subject matter - a concept so fraught with contradiction that every mathematical solution begs a dozen more questions.

Whether as anti-art, institutional critique, conceptualism, exploration of the immaterial or the dematerialization of the art object, the empty or near empty gallery has been a mainstay of contemporary art for almost fifty years. Ray Johnson responded to the popularity of Happenings by performing and exhibiting his own Nothings. In 1961 he turned off the electricity at the empty A/G Gallery and placed wooden dowels on the darkened staircase leading up to the space, making it hazardous (if not downright impossible) for anyone to even attempt to enter the space. In 1969 Robert Barry presented his “Closed Gallery” piece and the same year created a work for the Simon Fraser Institute in Vancouver entirely through telepathy. Art & Language exhibited air conditioning in 1971. Tom Friedman had the space above an empty pedestal cursed by a local witch. In 2001 Martin Creed won the prestigious Turner Prize for an exhibition that consisted of a vacant gallery with the lights turning on and off.³ Most recently Ron Terada exhibited an empty space at the Contemporary Art Gallery of Vancouver, with only the names of the exhibition catalogue benefactors stenciled on the walls.

One of the earliest examples was Yves Klein’s The Void at the Iris Clert Gallery in Paris, 1958. Klein removed all of the canvases from the gallery walls and painted over the windows. An extravagant opening was held on the eve of the artist’s birthday with 3000 guests in attendance, each paying the (then exorbitant) three-dollar admission fee. They were served a blue cocktail, which, unbeknownst to them, would cause them to piss blue for the next day.

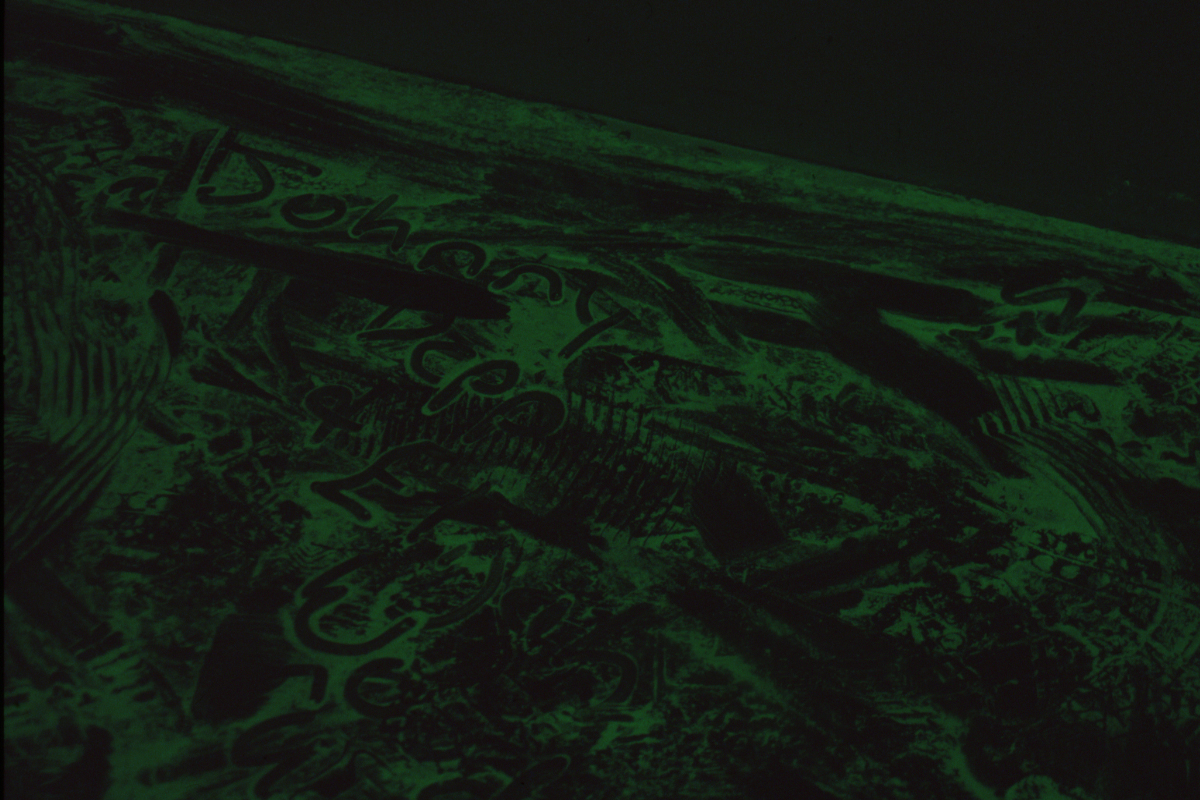

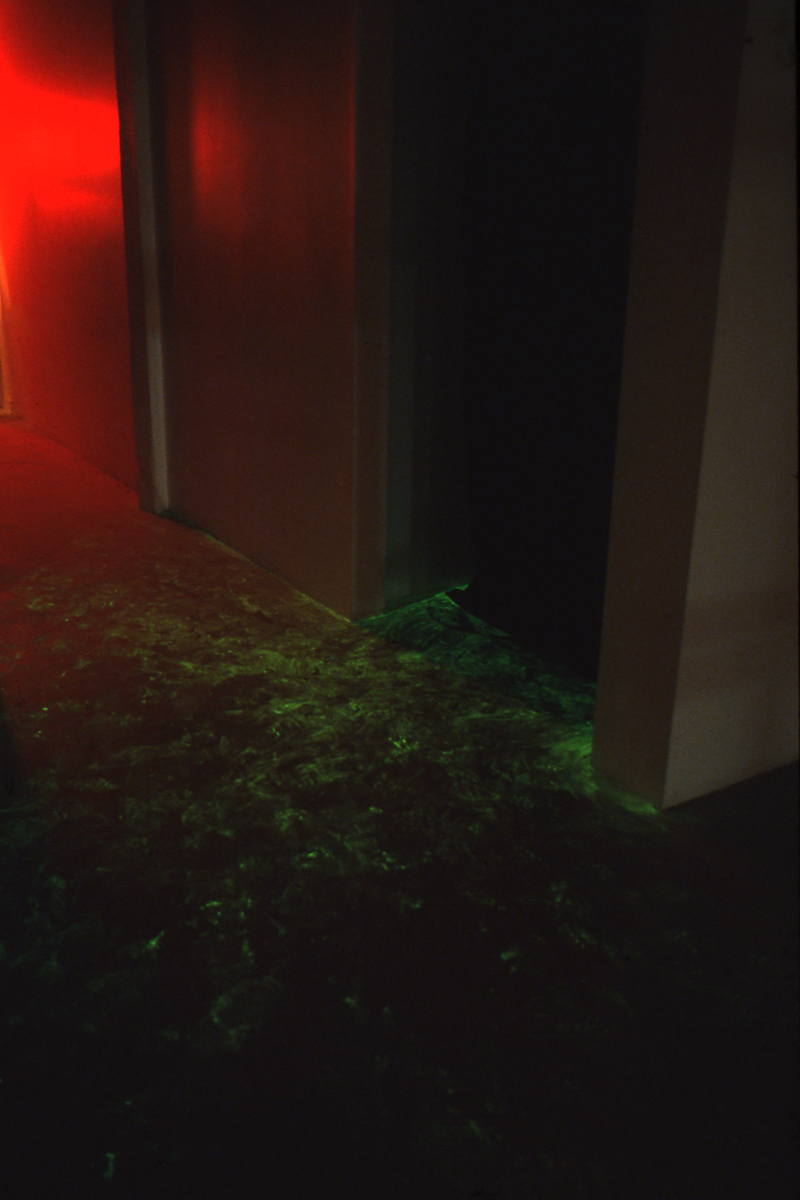

Levin Haegele’s Glow Space for 0.001 Percent Volume follows a similar tactic: the gallery visitors extend the exhibition space by inadvertently carrying the work away with them. A green phosphorescent pigment covers the floor of the empty, dark gallery back room. When visitors walk through the space the powder clings to their shoes and later, unexpectedly, once the powder has again been exposed to light, it is reactivated and begins to glow again. Perhaps in a darkened cinema or nightclub. Possibly in their home, discreetly, at the bottom of a closet.

The powder itself is the same kind used in commercial Exit signs, adding a layer of punning to the work. In 1961 George Brecht created his Word Event with the simple instruction of Exit. The title would imply that the work is linguistically based, but its actual function is the turning of an everyday event (responding to an exit sign, or even just exiting) into a performance. Haegele’s work concretises such an act – to activate the work, the viewer must leave it.

The constant flux of the installation – from luminous to dull, from contained to dispersed, from full to empty, from existing to vanishing – reflects the artist’s continuing practice of disruption and ephemerality.

The oft-told story of John Cage’s 1958 visit to an anechoic chamber has achieved legendary status in the history of nothing art. Through impedance-matched absorbers, the room was designed to eliminate all external noise and vibrations. Instead of silence, however, Cage heard two distinct sounds – a low pulsing noise and a constant singing high tone. He rushed to challenge the engineer, believing the soundproof room to be faulty. It was explained to him that the pulsing he heard was the sound of his own blood circulating and the higher pitch was the sound of his nervous system.

The anecdote, and Cage’s famous silent composition 4’33 that followed, illustrate the paradox of nothing.⁴ When a pianist sits and performs the score to 4’33” (three tacit movements) the ambient sounds in the room come into sharp focus. An audience member stifles a cough. The radiator hums. A chair leg scrapes the floor.

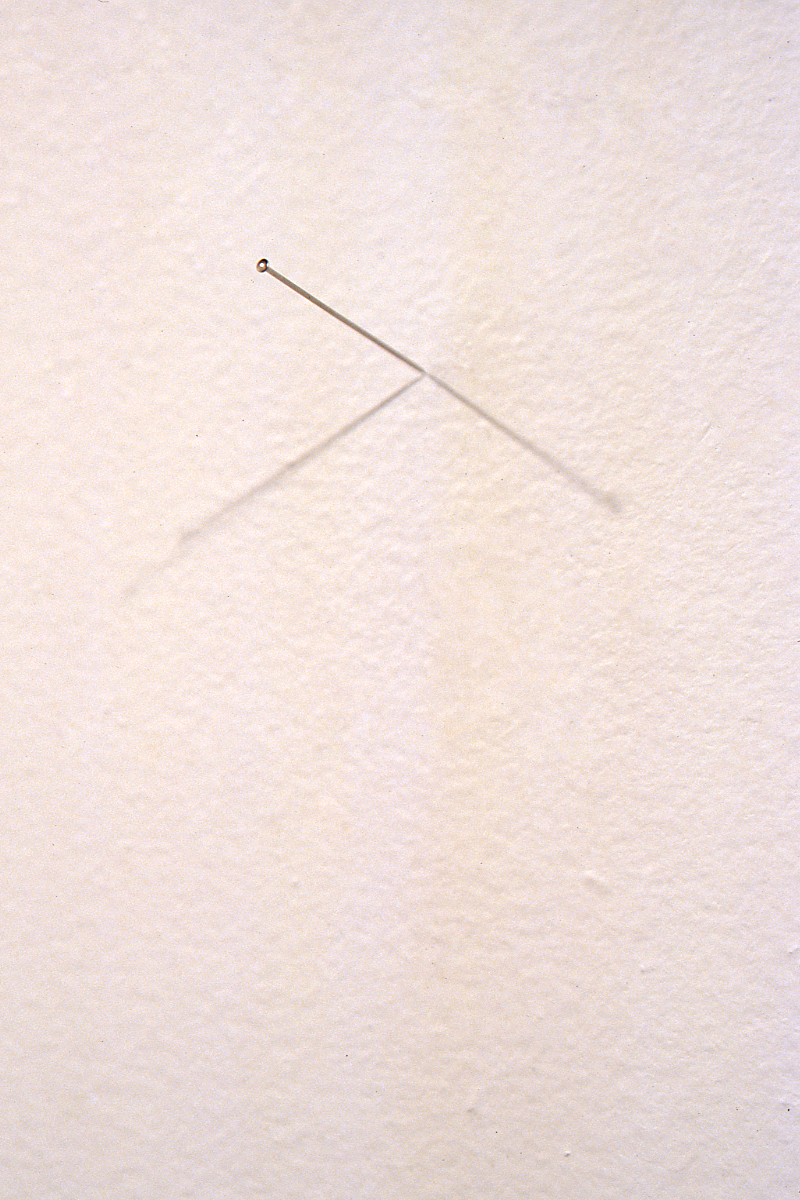

Ben Woodeson’s Point Blank sculpture is perhaps the visual equivalent. The single dressmaker’s pin gently held perpendicular to the gallery wall serves as an exclamation mark of sorts, in the otherwise barren gallery. A needle, no haystack. Its means of support is hidden but, once the initial sense of magic passes, the viewer deduces that an electromagnetic field is at work behind the scenes. This quick reflective pause draws our attention to the room’s other intangibles – the infrared light of the gallery security system,⁵ the countless songs and inane chatter of the radio waves, and other omnipresent electromagnetic fields that allow our cell phones, even compasses to function.

Woodeson uses electricity as his primary medium, but to such subtle ends that the intangible itself becomes the subject matter. At the Tramway Gallery in Glasgow, the artist introduced an inductance coil and transformer to the gallery pillar. When an electrical current is ran through the device the pillar expands slightly, in both length and width. Another work from 2003, Variable North, attempted to shift the galleries electromagnetic field through the use of 15 large magnets affixed the gallery walls.

Despite the considerable headway of sound-based art, sight is still privileged over hearing in the gallery - and the culture at large. From most strains of western philosophy to common platitudes such as “seeing is believing”, sight remains the ultimate “objective” sense. Possibly because we can direct our gaze and close our eyes but not our ears. Perhaps that we can see to the horizon, but not hear to it. When sound work does get included in gallery exhibitions they tend to be either ambient or musical in nature, often both. Dense layered loops or slow chiming atmospherics. Or about the culture that surrounds sound – speakers, records, rock stars, feedback.

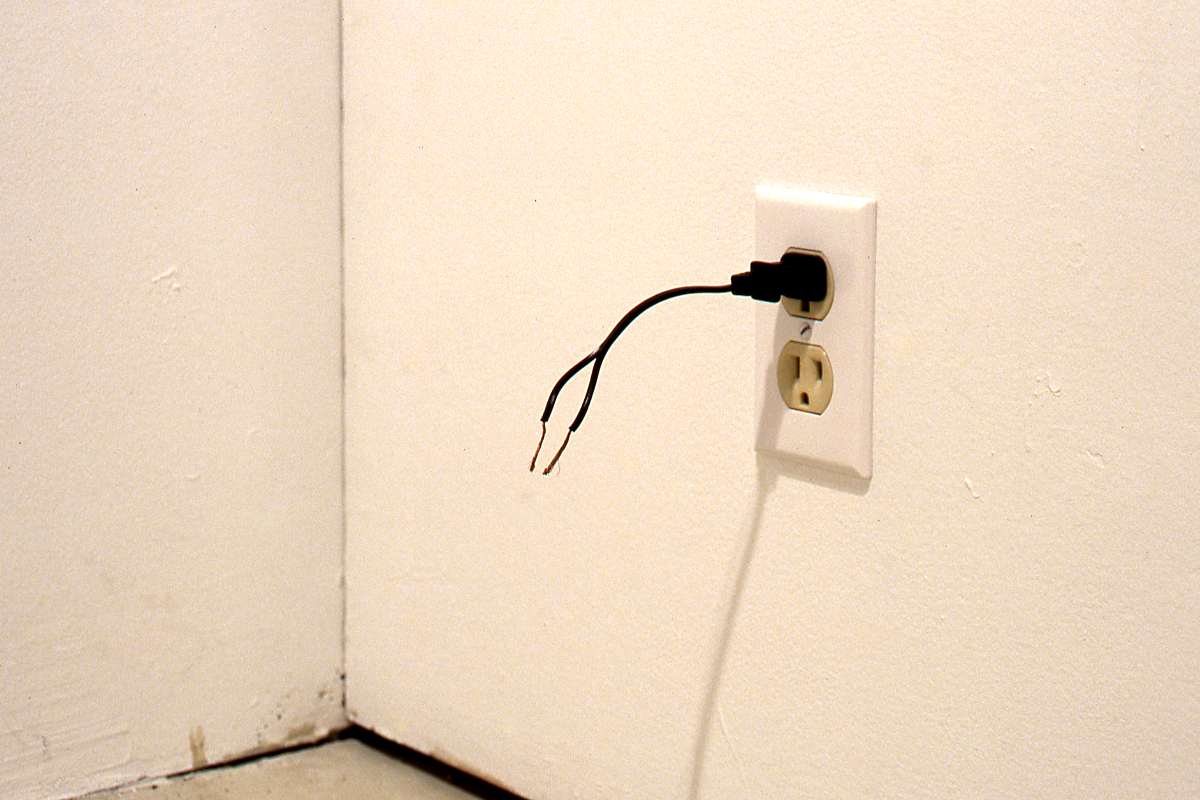

Myfawnwy Ashmore’s enarmoured euphorbia is a single second long and its means of amplification is hidden. Two wires discreetly hang from an electrical socket, daring the viewer to succumb to a childlike curiosity and touch them together. Potentially running the risk of electrocution, the participant is rewarded for their effort with a simple declaration of love.⁶ This quiet affirmation delicately explores electricity as a metaphor for love and communication - the spark, the magnetism, etc.

Rather than a simple act of ventriloquy, the voice is that of an anonymous small child – a wav file that the artist found online, where all information travels via electricity and everything is reduced to a number one or zero.

The artists/works in this exhibition are aligned with a new wave of committed conceptualists who are far less interested in agitation than their predecessors. Barry’s Closed Gallery, for example, was updated in 2003 with Jonathan Monk’s⁷ During the exhibition the gallery will be open, in which all the sounds and conversation from the empty gallery were broadcast outside the space via a transmitter radio. Unlike its prohibitive antecedent, here the empty gallery serves to encourage discussion and social interaction. The patricidal action of Robert Rauschenberg erasing a Willem De Kooning drawing in 1953 is replaced by Tom Friedman’s blank page from 1997 titled 1,000 Hours of Staring – a work about contemplation and trust.

Where Ray Johnson wanted to break your ankles, Levin Haegele just wants to make them glow a bit.

There is a warmth, domesticity and naiveté at play in 0.001 Percent Volume that is absent in many of the boundary breaking nothing works of the sixties. A simple seamstress’ pin, a child’s voice, debris on one’s boots – these couldn’t be more different from the grandiloquence of minimalism⁸ or the chilly detachment of conceptualism. These restrained and understated gestures have the ability to open up a striking set of possibilities with the utmost economy of means.